When Public Records Become Private Dossiers: How Data Brokers Make Us Vulnerable

Public anger about data privacy is usually directed at social media companies. Platforms like Facebook, Google, and TikTok collect vast amounts of user data - demographics, interests, location, browsing habits, and other online behavior, to power targeted advertising and maximize engagement. In practice, this data is often used to construct abstracted user representations - behavioral profiles, cohorts, or digital "fingerprints" designed to predict attention and influence outcomes, rather than to expose an individual's real-world identity.

There is no question that this model has caused significant harm, including psychological manipulation, distorted incentives, and a steady erosion of personal privacy. That focus, however, has also narrowed the privacy debate, leaving a quieter, less visible industry operating largely outside public scrutiny.

Away from news cycles, congressional hearings, and viral scandals, a parallel ecosystem has been compiling detailed profiles of ordinary people, not based on what they choose to share, but on what can be inferred or extracted from public and commercial records. These companies do not shape feeds or sell ads. They make money by collecting and selling personal information.

And unlike social media, where data is at least nominally exchanged for a service, this system functions without participation, consent, or meaningful awareness.

How Data Brokers Turn Scattered Facts Into Dossiers

Let's start with how this type of personal information, which is very different from the abstract behavioral "fingerprints" used in advertising, is collected in the first place. Nearly every interaction with society leaves small traces - address changes, utility accounts, phone records, registrations, transactions. Some institutions make certain information public by design - court filings, property deeds, business registrations, licensing records, and similar documents. On their own, these fragments do not amount to much.

Under the current law, the information is public and none of it is secret in isolation. But something fundamentally changes when those fragments are assembled into a single profile that reveals where someone lives, how long they have lived there, how much their home is worth, who they are related to, which phone numbers and email addresses they have used, and what legal or financial events appear in their past. And in some cases, how they are categorized or profiled based on inferred characteristics drawn from that data.

Through large-scale aggregation and indexing, what was once scattered across bureaucratic systems, commercial databases, and social platforms becomes a ready-made dossier. Unlike isolated records, these dossiers carry greater risk. They do not merely reflect public information - they reconstruct private lives, creating something that can function as a blueprint for misuse or abuse.

There is, of course, demand for this kind of information, and where demand exists, a market follows. Data brokers exist to meet it.

Why Aggregation Changes Everything

A property record at a county office requires effort to locate. A court docket may require knowing where to look and how to interpret it. A phone number alone tells you almost nothing. An email address without context is typically no more than a destination for untargeted, generic spam.

But when these fragments are compiled into a single profile, cross-referenced, timestamped, and made searchable - the barrier to misuse collapses.

Not all data brokers operate in the same way. Some focus on consumer-facing products, offering paid access to individual profiles that consolidate addresses, contact information, property records, court filings, and inferred relationships. Others operate almost entirely behind the scenes, selling bulk datasets or segmented lists to clients who are less interested in a specific person than in reaching a narrowly defined group.

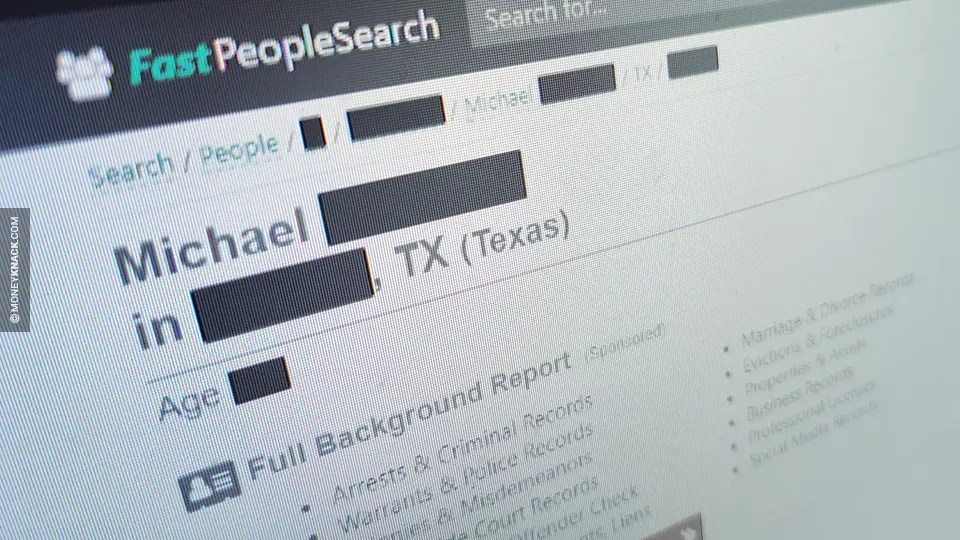

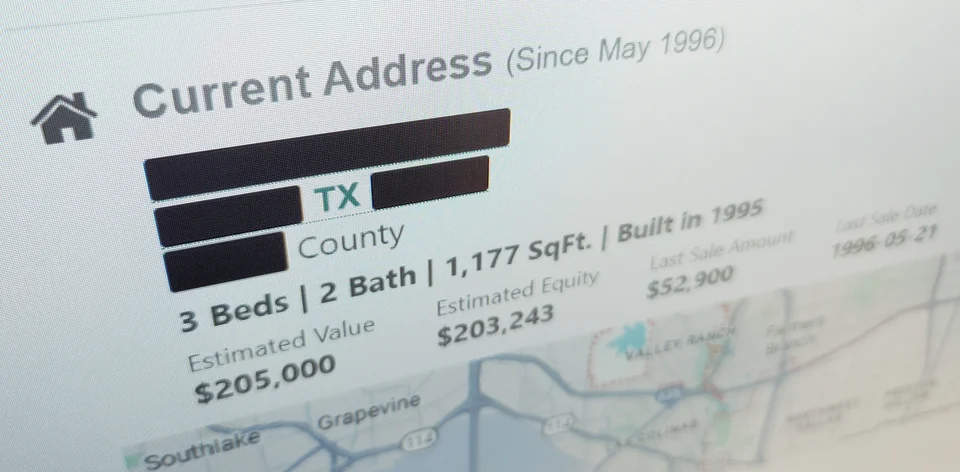

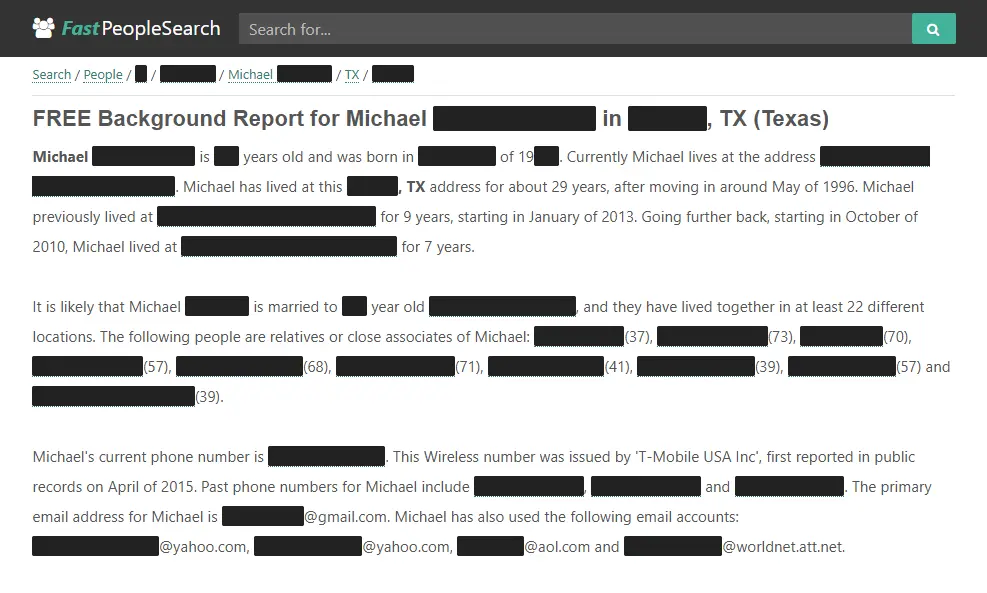

For someone seeking information about another person, the entry point is often very simple. Typing a person's name and an approximate location into a people-search site, or even just in a search engine, can surface a profile containing current and past addresses, phone numbers, email addresses, relatives, property details, and legal or financial records - information many people would not knowingly publish together, even if some of it is technically public.

Actual people-search profile, shown with personal information redacted.

For those seeking more detail, the ecosystem extends well beyond any single platform. Additional actors operate to further enrich and expand these profiles.

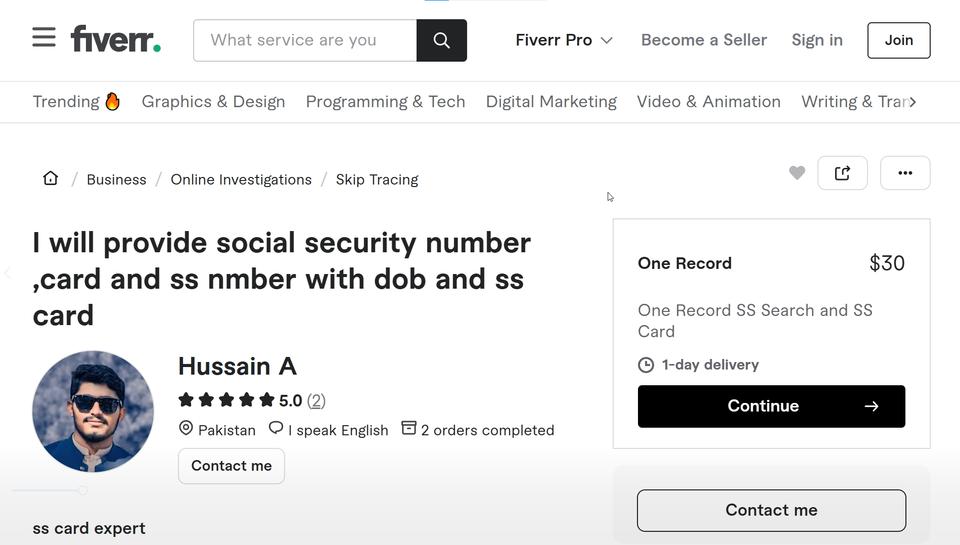

For instance, services like this can be found on freelance marketplaces such as Fiverr. Although such offerings violate Fiverr's terms of service, and may be illegal or fraudulent, they appear regularly and are removed only to resurface again. Listings advertised as "background checks", "identity verification", or "OSINT" (open-source intelligence) services sometimes claim to locate a person's Social Security number or produce detailed background reports containing other highly sensitive personal information. These listings often framed as verification or investigative work.

The effectiveness of these services depends on how much information is provided up front. The more identifiers already known, the easier it becomes to link additional records or validate an identity. And people-search websites often supply more than enough to make that possible.

Other brokers market lists designed to reach specific populations rather than named individuals. These lists may be segmented by age, income indicators, debt signals, language preference, homeownership status, or recent financial distress, and are commonly sold for marketing, lead generation, or outreach purposes.

Although such lists are often marketed under benign labels such as "consumer segments" or "audience categories," they facilitate highly targeted outreach to specific populations, including those facing financial or personal stress.

Aggregation enables forms of harm by removing the friction that scattered information once provided. When a profile reveals a person's current address, how long they have lived there, whether the property is owner-occupied, and who else is associated with that location, it lowers the practical barrier to harassment or physical targeting. What once required effort, persistence, and local knowledge, becomes immediately accessible to anyone with a search bar.

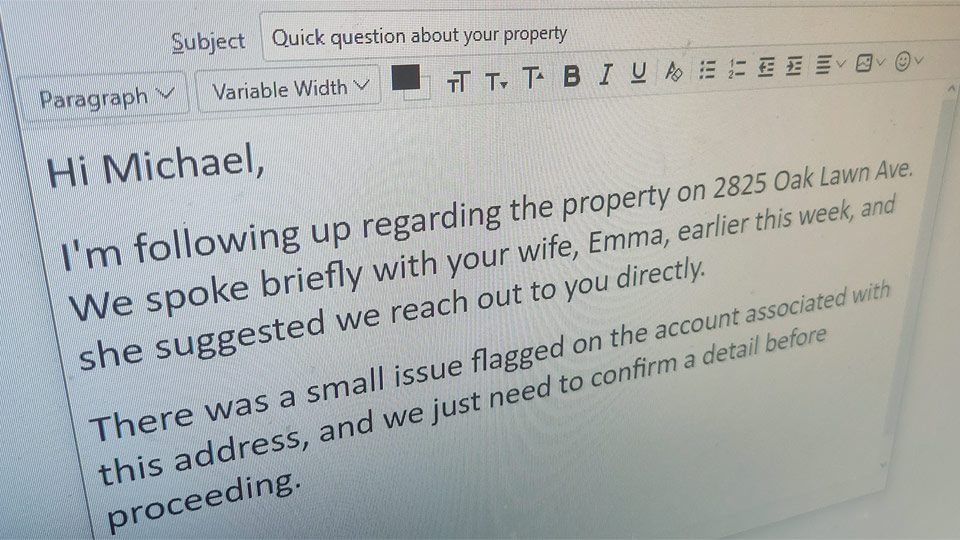

Aggregation makes deception easier. Social engineering and fraud depend on credibility, and aggregated profiles supply it. Details such as relatives' names, previous addresses, phone carriers, or long-used email accounts allow scammers to construct pretexts that sound informed rather than speculative. Calls or messages framed as routine follow-ups about a property, an account issue, or a request supposedly authorized by a family member sound typical and legitimate, making the contact easier to trust.

The risk compounds when these profiles are shared in hostile contexts. Publishing a person's information for intimidation or retaliation is commonly called "doxxing", but the underlying issue is not simply exposure. It is the creation of a consolidated targeting file that turns public records into a tool for harassment, aimed at an individual and, often, their family or close contacts.

For many people, the most immediate impact is psychological. The existence of a complete, searchable profile outside one's control can create a persistent sense of vulnerability. Because these profiles often include relatives, what begins as an individual privacy concern quickly extends to family safety.

These consequences are not just hypothetical. Victims of stalking have reported individuals targeting them using people-search sites to track moves in near real time. Survivors of domestic abuse have discovered their new addresses listed weeks after relocation. Journalists and activists have faced coordinated harassment fueled by readily available profiles. Ordinary people have been mistaken for criminals due to misattributed records.

In 2021, Epsilon Data Management, one of the largest marketing companies in the world, entered into a deferred prosecution agreement with the Department of Justice, under which it admitted that employees knowingly sold consumer data to perpetrators of mass-mail fraud schemes.

According to federal prosecutors, Epsilon sold modeled lists covering more than 30 million Americans to clients engaged in fraudulent sweepstakes and similar scams, which disproportionately targeted elderly and financially vulnerable individuals. The company agreed to pay $150 million after acknowledging that its data had been used to facilitate widespread fraud.

Legal, but Only Technically

If you are thinking that certaintly must be illegal, you are right - it must be. But it is not. In the United States most of this activity is lawful, largely because privacy law has not kept pace with the scale and consequences of modern data aggregation.

The United States does not have one clear federal privacy law. Instead, personal data is governed by a mix of narrow rules that apply only in specific situations. Health data, for example, is protected under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), while the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) restricts the use of consumer data for employment, housing, credit, and insurance decisions. That is why people-search websites and other data brokers state that their reports may not be used for those purposes.

But those disclaimers exist primarily to limit legal liability, not to protect people. They do nothing to prevent stalking, harassment, targeted fraud, or intimidation. As long as the information is not used to deny someone a job, an apartment, or a loan, its collection, aggregation, and sale largely fall outside existing legal protections.

In other words, the law draws a line around how data may be used, while leaving largely unregulated how much of it can be collected, combined, and exposed in the first place.

What Individuals Can Do (For Now)

State-level privacy laws have begun to challenge this model, granting some residents opt-out rights and placing limits on certain data sales. But enforcement remains uneven, opt-out processes are often deliberately burdensome, and the default condition is still exposure.

New proposals for expanded children's online privacy protections at both the state and federal level promise greater safety, largely by requiring platforms to determine who is a child and who is not, which in practice means collecting and retaining even more personal information, and which is, of course, exactly what this ecosystem needs.

Removing personal information from people-search and data broker sites is often frustrating and discouraging. Each site maintains its own removal process, often involving identity verification and obscure web forms. There is no comprehensive federal law requiring most data brokers to honor opt-out requests at all, and even when removals are granted, nothing prevents the same information from being re-collected, re-combined, and republished weeks or months later.

There is no single fix. Some steps can reduce risk, including setting alerts for your name and address, monitoring credit reports, placing credit freezes or fraud alerts if you suspect identity misuse, and regularly searching your name on people-search sites and search engines. Where state law requires it, some sites also offer "Do Not Sell" or opt-out tools.

But these steps take time and constant effort. They put the responsibility on individuals to manage their own exposure, rather than on the companies collecting and selling the data, and they are unrealistic for most people to keep up with over the long term.

This burden has also created a market for paid data-removal services that promise to manage the process on a user's behalf. These services can reduce some of the manual effort, but they come at a financial cost and do not solve the underlying problem. As long as data breaches continue, public records remain accessible, and the collection, aggregation, and sale of personal information is broadly legal - removal becomes a perpetual cat-and-mouse game.

Ultimately, many privacy advocates argue that meaningful protection will require moving beyond piecemeal regulation and toward prohibiting the commercial trade in personal data altogether, as current policies often fail to keep pace with the industry's practices and loopholes, leaving individuals responsible for defending themselves against systems they did not consent to and cannot realistically control.

Still, people who want to push for change can support organizations that focus on digital rights and privacy, such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which tracks data broker practices and advocates for stronger safeguards. Contacting state and federal representatives to support comprehensive privacy legislation, including limits on data brokerage and stronger consent requirements, can also help keep the issue on the political agenda.

These steps may not offer immediate protection, but they are among the few ways individuals can influence whether this system continues to operate largely unchecked.

Without sustained public pressure, the market will keep expanding, leaving individuals to absorb the harms while data brokers and buyers capture the gains. Silence, in this market, functions as permission.

Appendix: What Can Be Done

Collective and Systemic Pushback

Contact elected officials. Find your members of Congress at house.gov and senate.gov by entering your ZIP code. Call or email their offices and ask where they stand on comprehensive federal privacy legislation, including limits on data brokerage and stronger consent requirements. You do not need legal language. A short message stating concern about data brokers and personal data sales is enough.

Support privacy advocacy organizations. Organizations such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and Fight for the Future track data broker practices, publish research, and advocate for stronger privacy laws. Supporting their work financially or by sharing their campaigns, helps sustain legal challenges and policy pressure.

Engage regulators. File complaints with agencies like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) or the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) if you believe personal data is being misused or sold irresponsibly. Complaints help regulators identify patterns and justify investigations, even when no immediate action follows.

Participate in rulemaking. Federal agencies regularly open public comment periods on proposed rules. Submitting a comment, even a short one, on issues such as Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) updates or data broker oversight places public concerns into the formal record.

Support state-level privacy efforts. Follow and support initiatives like The California Delete Act, which aims to create a centralized data-deletion mechanism. State laws often become templates for broader national reforms.

Individual Actions

Reduce unnecessary data sharing. Limit the personal information made public on social media profiles. Avoid online quizzes, personality tests, and sweepstakes, which are common data-collection tools.

Use separation where possible. Use alternate email addresses and phone numbers for non-essential services. Avoid reusing the same identifiers across platforms.

Opt out directly. Many data brokers allow opt-out or deletion requests, though each has its own process. Requests may need to be repeated periodically, as profiles are often regenerated.

Consider data-removal services

Paid services such as DeleteMe or Incogni can manage opt-out requests on your behalf.

References

- Department of Justice, https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/marketing-company-agrees-pay-150-million-facilitating-elder-fraud-schemes